A Voice for the Underdog: Championing Civil Rights at the EEOC, SCOTUS, and Beyond

What drives someone to dedicate their entire legal career to fighting for the little guy? For Karla Gilbride, it began early—a fierce intolerance for injustice, amplified by her own lived experience as a blind person in a world that often told her, "No, you can't."

A path that started with mock trial competitions in high school led her to public interest advocacy at Public Justice and an unforgettable day when Karla stood before the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court and literally changed minds. A year later, after a presidential appointment and a Senate confirmation, she took on the role of General Counsel at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Now the deputy director of Litigation at Public Citizen, she continues her mission of standing up to power imbalances and helping underdogs speak their truth.

Listen as Karla shares stories about how her lived experience informs her perspective, preparing for a Supreme Court argument, navigating a Senate hearing, and why representing migrant farm workers in a California courtroom ranks among her personally meaningful professional achievements.

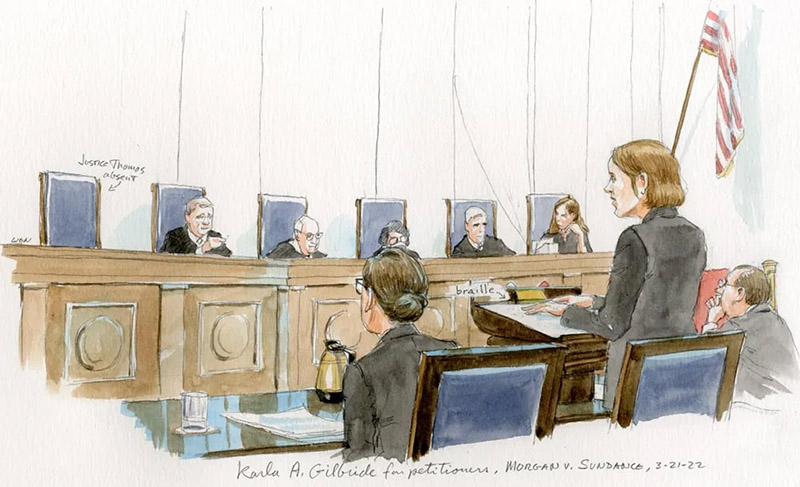

Karla Gilbride arguing for Robyn Morgan before the U.S. Supreme Court. (Sketch by Art Lien)

Guest Insights

- [02:02] The start of a lifelong mission to fight injustice and represent the underdog.

- [04:20] Personal experiences with discrimination as a blind person.

- [10:33] From Ninth Circuit clerk to Disability Rights Advocates to Public Justice.

- [12:36] Appearing before the U.S. Supreme Court.

- [18:53] Preparing for a SCOTUS argument.

- [20:58] Getting a favorable opinion and take-home swag.

- [26:28] Senate confirmation and joining the EEOC as General Counsel.

- [36:10] New chapter at Public Citizen.

Links From This Episode

02:02 - The start of a lifelong mission to fight injustice and represent the underdog.

04:20 - Personal experiences with discrimination as a blind person.

10:33 - From Ninth Circuit clerk to Disability Rights Advocates to Public Justice.

12:36 - Appearing before the U.S. Supreme Court.

18:53 - Preparing for a SCOTUS argument.

20:58 - Getting a favorable opinion and take-home swag.

26:28 - Senate confirmation and joining the EEOC as General Counsel.

28:10 - New chapter at Public Citizen.

John Reed: [00:00:09] The law is supposed to be about fairness. I should know; I went to law school and watched the Schoolhouse Rock Constitution episode. But I'm not naive. The law and we humans are imperfect.

As we all know, power, when abused, corrupts. An employer. A corporation. A president with a bad combover. They can use their positions to push people around, deny opportunities, slam doors shut. And if you happen to be on the receiving end of that power imbalance, you're told no. A lot. You are considered to be less than.

But sometimes being pushed down lights a fire. You may lack power, but because you have resolve, you can use that fire as a force for change. And if you're really lucky, you have an ally unafraid to speak truth to power.

My guest today is both of those—a fighter and an ally. She was bullied growing up blind, and she still encounters disability discrimination today. The denials, the assumptions, the mistreatment, they fuel her fire. She champions the little guy, the oppressed, the underdog. She relies on the law or challenges it to seek fairness and justice.

Karla Gilbride is the public interest lawyer's public interest lawyer. You'll hear about her career as a civil rights advocate, her argument before the US Supreme Court and the unique experience she had there, her time as General Counsel at the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (the top attorney at that agency), and her unique perspective as both a person and a lawyer with blindness.

Welcome to the podcast, Karla.

Karla Gilbride: [00:01:45] Thanks so much for having me.

John Reed: [00:01:47] I'm very excited to speak with you, and there are a lot of things, a lot of experiences, that I want to ask you about. You've dedicated most of your legal career to public interest law and the nonprofit world. Where did that dedication originate?

Karla Gilbride: [00:02:02] I have always, from a young age, been very passionate and very angry about any sort of injustice or what I sort of perceive as bullying, somebody taking advantage of being stronger, of having more power, and using that power to bully or abuse somebody else. So, what motivated me to get a law degree and to become a litigator was wanting to remedy those sorts of imbalances and that sort of bullying. And so, I've always had a passion for sort of representing the underdog, the individual, the worker, the person who's experiencing discrimination. And so, I have done some work with plaintiff's law firms, but for the most part, where I've been able to channel those passions has been working for nonprofits and doing law in the public interest.

John Reed: [00:02:52] I talk to guests and they tell me either they came out of the womb arguing and ready to go into litigation or that they came to it later. You sound like more of the former than the latter. Were there indications in your adolescence, in your early years? Maybe your parents or somebody said, "Oh, yeah. You're going to be a lawyer, you're going to be a litigator."

Karla Gilbride: [00:03:13] I definitely got that from my parents as a kid. And I think what I understood lawyers to be, based on the way my parents described it, was people who liked to argue. And I definitely fit that description. I always enjoyed both the written word and the spoken word, and using words as my tools. Socially, talking to people, socializing with friends.

But also, as a totally blind kid, I didn't have a lot of opportunities to compete in sports with my peers. So, using words were sort of my way of competing. So, I did the speech and debate team in high school. I did a lot of public speaking. I also joined the mock trial team, and I got to play a lawyer doing examinations of witnesses. So even as a teenager, I was definitely testing those waters of what it might be like to be a lawyer.

John Reed: [00:04:02] Excuse me, for what may be kind of one of those “duh” questions, but did your lived experience with blindness, did you have your own experiences of that imbalance or being bullied? I hope not. But that kind of unfairness, that also fueled your interest in what you do now?

Karla Gilbride: [00:04:20] I definitely did have personal experiences. I, for the most part, had good experiences with my peers, but sometimes kids are mean to each other, and I certainly experienced a little bit of that growing up. But I think what was more formative was with adults, when I experienced teachers telling me you can't do something.

So, I mentioned sports a minute ago. Sometimes in gym class, being told, "Oh, it's too dangerous for you to do this activity. You should sit this out." So being excluded or told that something was off-limits to me. That sort of unfairness very much rankled me as a kid. The same thing would happen later when I was looking to do volunteer activities or my first summer jobs. Getting questions about “well, how would you do that as a blind person,” was my first brush with the sorts of barriers that people with disabilities experience in the workplace. And I think that also gave me some of that fire in the belly to go ahead and be a lawyer and advocate because I knew what that felt like to be told, "No, you can't do something."

John Reed: [00:05:23] We've talked before, and I've told you that I'm very proud I'm involved with Leader Dogs for the Blind. I unfortunately hear stories all the time about disability discrimination, vision loss discrimination, particularly, not necessarily in the workplace, but in people's day-to-day lives. Refusal of service at restaurants or stores. One that I didn't know about until recently—rideshare discrimination. General accessibility. You've talked about your childhood and high school. Have you experienced those types of things as an adult?

Karla Gilbride: [00:05:53] Absolutely. Certainly, as a guide dog handler. I have had three guide dogs, and I have one right now who's laying in the bed next to me snoring away. And when I travel places with my guide dog, I have experienced frequent denials of service, both from rideshare drivers and, previous to that in the olden days, cab drivers saying, "You know, I won't take you because of your dog." Other service establishments, restaurants, trying to kick us out because I was traveling with the dog. And sometimes it happens even when I'm not traveling with my dog, just as a blind person, people saying, "You know, we're not sure it's safe for you to do this activity."

I went with some friends to do a ropes course, a ziplining course. And I've done those sorts of activities many times without any problem. But one outfitter didn't think it was safe and didn't want to accommodate my friends and me because some of us were blind. So, that's certainly an experience, just traveling through the world that unfortunately, as a person with a disability, you are going to experience those sorts of doors slammed in your face.

And the rideshare is a very endemic problem in that regard. There's a lot of that going on, and there've been, I believe there's currently a Department of Justice lawsuit about discrimination against people with disabilities from Uber. So, I'm glad that's being taken on systemically, but it's difficult because the drivers keep changing. Even if the company says they're cracking down on it, it's difficult when you have so many different drivers that you're interacting with.

John Reed: [00:07:28] Yeah. And my understanding is that there's no teeth, right? I think you can report on the app, but a lot of people have said it doesn't go anywhere.

Karla Gilbride: [00:07:36] Right, so you can file a complaint, and both Lyft and Uber are supposed to follow up. The drivers have recourse to say why they denied or why they canceled. But certainly, if it happens more than once, it's supposed to be grounds for the driver being kicked off the platform. One thing that is difficult, though, is just not knowing for sure what the follow-through is.

Again, as I said, there's so much turnover that even if an individual driver is kicked off the platform, will the next driver who comes along know about that and be deterred from not doing the same thing?

John Reed: [00:08:12] So I have to ask, have you ever played the lawyer card when that happens?

Karla Gilbride: [00:08:14] Um, I certainly played the lawyer card with various service denials. I don't think I've done it with Lyft and Uber. I just tell them, "I'll show you on the app where it says you have to take service dogs because they do have a very prominent disclosure statement on there. Usually, when I say I'm going on the app right now to report you, you could lose your ability to drive. Most of the time, that works. Most of them do say, “Okay, fine, I'll take you.”

Speaking up and advocating for your rights, whether you're a lawyer or not, is usually effective. Not always, but you won't get anywhere if you don't speak up. So, I always tell people, speak up. Don't get angry and yell, but just be firm and explain what the rules are and what the consequences will be. And then, hopefully, that will be enough to change their behavior.

John Reed: [00:09:01] Thank you for that. I think there's a lot of people that would benefit from hearing that experience.

Let's go back for a second. You've had this lifelong drive to be a lawyer, to do what you do, but you weren't the traditional poli sci-philosophy-history-prelaw student in college. Talk about that.

Karla Gilbride: [00:09:20] Sure. So, I've always had a fascination with how people learn language and the diversity of ways that people communicate. And so, I was a linguistics major in college, and I was a psychology minor. And so, the way I put those two things together was I studied language acquisition in kids, and particularly how it varies with kids who are typically developing neurologically vs. kids with autism and other types of neurodivergence.

I went and studied kids in Massachusetts who came in and played with their parents in the lab, and then we videotaped their interactions with their parents and how they communicated and how they used language. And I reviewed those videos and transcribed them and coded them and thought that maybe that sort of research was something that would interest me. But my passion for justice that I was talking about earlier ultimately led me to law school instead.

John Reed: [00:10:13] So interesting. You started your career progression: Ninth Circuit clerkship, three years at Disability Rights Advocate, plaintiff-side law firm handling various discrimination cases, and then eight years at Public Justice. Talk us through those moves and your evolution to a director role at Public Justice.

Karla Gilbride: [00:10:33] Sure. The reason for leaving Disciplinary Rights Advocates was largely a personal one. My family is from the East Coast. And at that point, I had been out west for a few years, and I wanted to get back to be closer to my family in New York. So, I took a job with a plaintiff's firm in Washington, D.C., which was just a few hours' trip instead of across the country. And I've been back here in D.C. ever since.

But the next move, the one to Public Justice, what I realized I really enjoyed about practicing law was the appellate work, and putting together arguments, and making the most compelling case to a judge. Which you get to do in district court as well, but a lot of what I was doing at the law firm was negotiating settlements with employers and dealing with the day-to-day of discovery in our cases that stretched out for years and years. And the nice thing about appellate work is that you get a case that's already reached a conclusion, and you really get to focus in on the legal issues and make the best case that you can and do it in a pretty short amount of time in many, many, many cases. And that was what I really wanted to do.

And so, at Public Justice, I had the opportunity to become more of an appellate specialist, where I would become an expert in a few areas of law, and I could work on a case for a month or two, handle the appeal, and then take on another case. So, it gave me a chance to really hone my craft of writing briefs and giving oral arguments without having to stick with the same case for years and years through every little up and down of the discovery process. And that's something I really enjoyed, and that's why I stayed at Public Justice as long as I did, and the wonderful colleagues and connections that I made there. But I really took to the appellate work, and enjoyed doing that for a good chunk of my career.

John Reed: [00:12:29] But not just any appellate work. You argued before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Karla Gilbride: [00:12:36] I did, yes, I argued a case there in 2022. That was a really unforgettable experience. I fortunately had worked on the sorts of issues that that case presented in several other cases. So, I felt quite confident that I really knew the legal issues well by the time this case came along.

The case was called Morgan vs. Sundance, and like many of my cases, it involved a worker, actually a group of workers who worked for a Taco Bell franchise in Iowa. And they alleged that they weren't getting paid overtime when they worked more than 40 hours a week. They wanted to file a lawsuit about that. And Robin Morgan was the lead plaintiff. She filed this case on behalf of herself and her coworkers. And the case went along for almost two years with the employer making arguments about why she shouldn't be entitled to that overtime.

And, ultimately, when the employer was not successful in getting the case dismissed, they brought up a new argument, which was that when she had applied for her job, she had agreed to certain sort of fine-print terms. And one of those terms was, you will not file a lawsuit against us. If you have a dispute, you'll handle it in a private arbitration forum. So, they said, “Well, this case shouldn't even be in court at all. It should be in arbitration.” But because the case had been going on for so long in court and they had never made this argument before about it needing to go to arbitration instead, Robin Morgan said, “You waited too long to invoke that arbitration agreement; you waived it.” So that's sort of a legal term for, you know, you snooze, you lose. If you don't assert an argument, you can't make it.

John Reed: [00:14:15] By the way, I like “you snooze, you lose” better.

Karla Gilbride: [00:14:18] So what wound up at the Supreme Court was when you're arguing waiver in the context of an arbitration agreement, is it the same legal test that you used for waiver of any other type of contractual right? Or is there a special arbitration-specific test? And the courts below, in the Eighth Circuit, and most other circuits had said there's a special arbitration-specific waiver test. And our argument was that arbitration agreements should be treated like any other contract. That's what the Supreme Court has said many, many times. And that's, that should be the case here, which means it should be actually easier for her to prove waiver, because the regular old contract test was easier than this arbitration-specific test that the courts had made up. And so, I got to argue that case at the U.S. Supreme Court.

John Reed: [00:15:11] Hold on, I want to stop you because I want to break this down because there's so much I want to ask you.

Let's go back because I think it would help people to know. How did that case come to you? How did Robin Morgan get to you?

Karla Gilbride: [00:15:24] So she had won her case at the district court, and then when she lost her case at the Eighth Circuit, there was a very strong dissent from one of the three judges on that panel. And that judge in dissent pointed out that there was a circuit split and kind of teed up the issue like, "Hey, I know, the Eighth Circuit has this precedent, but I think that precedent's wrong. And there's a couple other circuits out there that don't do the same thing we do in the Eighth Circuit."

So, when you have a dissenting judge who kind of tees up a circuit split like that, sometimes people will call that cert bait. It's like they're saying, "Hey, Supreme Court, you should look at this." And so, Robin's lawyers thought the same thing. And I think they may have even been approached by some other people who do a lot of Supreme Court arguments, but they came to Public Justice because we had specialized in these issues around mandatory arbitration in the workforce and had done a lot of these cases about waivers.

So, they thought, we want to go to the experts to first of all make sure this is a case we should petition for cert to the Supreme Court, because you know that you don't always want to do that in every case. So really, they wanted our advice about is this a good case to petition for cert, and if so, would you all want to handle it. I didn't meet Robin at first. I met her trial counsel. I did, later on, get to meet her and get to talk with her.

One sort of sad thing about the case and about what was going on at that time is that the court was still closed to the public because of the COVID-19 pandemic. So, the only people who were allowed in the courtroom were arguing counsel, court personnel, and media. Robin had wanted to see her case argued at the Supreme Court. And so, I asked if she could attend, and they said no; no members of the public. And I thought she's really not a member of the public. This is her case. She has a right to be there, but that was what they said. So, she had to just listen to the audio, like everybody else who wasn't allowed to go into the courtroom.

Another funny story about that argument is that my mom and my husband were both listening to the audio together on a laptop, and they said, we were staring at this blank screen because we're so used to looking at videos. But it was, it's audio only. So, one of the only visuals that we really have of Supreme Court arguments are the renderings that the sketch artist makes. And there was a long-time sketch artist who had covered all the Supreme Court arguments for many, many years. His name was Art Lien. I think he's since retired, but he was there the day of my argument. And when I was reading my notes at the lectern, I was reading them in braille. And so, in the sketch from the court from that day's court argument, he shows my hands on the braille paper with a little arrow indicating with the word "braille."

So, I thought that was a pretty cool demonstration and educational public service announcement for people to see a blind person arguing and how braille can be used to sort of level the playing field.

John Reed: [00:18:35] That is totally cool. That's really, really great.

Let's talk about preparing. You are one of so few who has had that opportunity. How does one prepare to argue before the Supreme Court as opposed to the Eighth Circuit?

Karla Gilbride: [00:18:53] I mean, maybe if you argue before the Supreme Court a lot, it's not that different, but for me, having never argued there before, it was a lot more preparation. For another type of appellate argument, I might do one or two moot courts with other lawyers asking me questions, playing the role of the judges, and putting me through practice answers. With my Supreme Court argument, I think I did five moots, and I recorded several of them, and I had another colleague sit and take notes on all of the questions and my answers so that I could study them in detail and write down better answers to try to give the next time. So, there was a lot of sort of iterative study and practice and getting lots of feedback from experienced practitioners and from people who have argued before the Supreme Court.

Another thing I did was I listened to many, many, many arguments so that I could hear the types of questions that the justices ask, how they handled these types of issues. So, I listened to other arguments involving arbitration, involving similar types of legal issues to what I was going to be arguing. And listened to my opposing counsel, who was a very experienced oral advocate, Paul Clement. So, I listened to his other arguments so I could get a feel for the way he might handle his portion of the argument and how to be prepared to respond to that.

One nice thing about the Supreme Court is that you know in advance who your judges are going to be. So, you can kind of anticipate the types of things they're going to ask and be prepared to tailor your responses to your audience.

John Reed: [00:20:30] That's such an interesting point because you don't necessarily know who you're going to pull on an appellate panel at the circuit level, whereas not only do you know who you're going to get amongst the justices, all nine of them, but you can study them, the history of their opinions, their thinking, et cetera. That seems like it, believe it or not— it sounds strange—might make it a little easier.

Karla Gilbride: [00:20:50] It does in a way. I mean, it's sort of like a closed-book exam in, a sense. You know, the material you're studying. There isn't a lot of last-minute surprises. Of course, it's sometimes easier said than done to convince them. They can also play off of each other in interesting ways.

I mean, one thing about being up there and arguing is it's a very hot bench, and you sometimes have limited time to get your answer out before you get interrupted, and then they'll stack questions on top of each other. One of them will ask a question, and then another one will say, “Oh, that reminds me.” And now you're answering two or three questions. Keeping all of that in your mind and then prioritizing what is most important to get out first before you get interrupted again, I would say, is one of the difficulties of arguing to nine people and nine very animated people who have a lot to say, compared to some appellate panels that can be quieter.

John Reed: [00:21:45] If you've got multiple questions, do you have to prioritize not only the question, but the seniority of the justice or the impact of that justice on the case?

Karla Gilbride: [00:21:55] I think impact on the case, perhaps, is paramount. I mean, you can try to take them in the order in which they were presented, but in terms of what perhaps you spend the most time on, and really try to drill down to make sure that they're satisfied insofar as you can make them satisfied, is you have to try to count the votes that you need.

If you think you already have somebody's vote, or you're pretty confident that they're going to rule for you, of course, you want to be polite to them, but they're not as important as the one who you think is on the fence.

John Reed: [00:22:25] I have been to the Supreme Court, not when it was in session. It is a daunting place. Talk about being in the court, the feeling of it, your presence there, and how you got acclimated to it.

[00:22:38] Karla Gilbride: Well, there is a lot of history in that building, in that room. That was one thing that certainly struck me right away was standing up there and thinking about all of the historic arguments that have been made and all of the legal luminaries who have stood where I was standing. That's a heavy thing and just an amazing feeling.

I did have a chance to go into the courtroom before, early in the morning, right when the building opened. I had reached out to the court to talk about what accommodations I would need or to argue, the main one being a way to mark the passage of time. So, there's a clock, a timer that counts down visually, but I wanted to have some sort of an auditory cue to when I was running out of time. When I had two minutes left, one minute left, et cetera. So, we were discussing how to do that, and I met the marshal who was going to escort me and who I had been talking to about the timekeeping issue. And he showed me where I would be sitting, where I would be standing at the lectern, and where the justices would be sitting.

He actually did something that I thought was really neat, which I hadn't even thought about asking him to do, but he said, "I can show you where each of them sits." And he stood behind each of their chairs, but sort of walked around to where each of their voices would be coming from so that I could get that spatial audio of here's where the Chief Justice sits, and here's where Justice Alito sits, and here's where Justice Sotomayor will be. Which was very helpful when I was arguing because in the room it actually does make a pretty big difference from the person who's right in front of you to the person in the middle, to the person who's on the far ends. And it helped me to identify who was speaking at any given time.

John Reed: [00:24:21] Is that like standard operating procedure? I've never heard of it, but then again, I don't think I would've had occasion to hear of it, but that just sounds so personalized, so cool.

Karla Gilbride: [00:24:29] I don't know if it's ever happened before or if this is something that he just came up with on his own. But I agree. It was very thoughtful and a very personal touch.

Another neat thing that they do at the Supreme Court, which they do do for everyone, but it's a neat memento, is at each space at counsel table, they have a quill, like a feather, to represent an old-fashioned quill pen. So, when you leave after your Supreme Court argument, you can take your feather with you as a symbol of having argued a case and sat at counsel table.

John Reed: [00:25:05] Did not know that either. And that's really cool too.

Karla Gilbride: [00:25:09] In the room where I'm speaking to you, which is my home office, I have a bookcase, and up on the bookcase is my Supreme Court feather.

John Reed: [00:25:16] I should also mention that Slate Magazine described your performance at the Supreme Court as "one of those rare arguments in which you can hear an advocate changing the court's mind in real time." I can't imagine a bigger compliment.

Karla Gilbride: [00:25:33] Yeah, that was really special to read. Actually, I'm a little embarrassed to share this, but if you listen to the recording, and I don't know that this is what the author of that piece in Slate was referring to, but there is a spot on the recording of the oral argument where Justice Breyer was talking to somebody—I'm not sure whoever he was next to— and you can hear him say, "I think I changed my mind."

John Reed: [00:25:58] Okay, Karla, is that the ringtone on your phone?

Karla Gilbride: [00:26:03] Yeah. I couldn't hear it in real time as I was arguing, but a friend pointed it out to me and said, "Did you hear what Breyer said?" And when you listen to it, that is what he says.

John Reed: [00:26:13] As if that wasn't momentous enough, it's not like your career stopped there. After Public Justice, it was the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Did you pursue them? Did you get on their radar? How did all that kind of transpire?

Karla Gilbride: [00:26:28] I did not pursue them. I certainly looked up to the EEOC, and a lot of very important developments in the law around civil rights and employment discrimination have come out of the EEOC. So, I held the EEOC in very high regard, but it wasn't particularly something that I had as part of my career plan to work there. It really just fortuitously came to pass that I guess I came to be on their radar screen as somebody who could be a good fit. And so, I got a call saying, “Would you be interested in being nominated to this position as general counsel at the EEOC.”

And what the general counsel does in that agency, which is a little different. When you hear about general counsels, they're often giving legal advice to a corporation or to an agency. And what the general counsel at EEOC does is actually coordinate and sort of manage the affirmative litigation that the agency does. So, decide what lawsuits to bring, and set the legal priorities and strategy for the litigation program. And that was a very exciting opportunity. So, when I was asked, “Would you be interested?” I said, “Absolutely.” But it was not something I pursued or really expected.

John Reed: [00:27:43] As if being grilled by nine justices wasn't enough, now you've got a Senate confirmation. Talk about preparing for that and what the hearings were like.

Karla Gilbride: [00:27:53] Well, there are more committee members than there are Supreme Court justices, but I have to say that, I think on balance, Supreme Court justices ask tougher questions.

I did have a chance to prepare, and the EEOC has the Office of Communications and Legislative Affairs, and they had reached out to me once I was nominated to give me some briefing materials about what I could expect from the confirmation process. I had talked about doing moots for the court argument. They actually did moots for the confirmation hearing with me, where they played the roles of senators.

Some played the roles of senators asking softball questions. Some played the roles of senators asking more probing or hostile questions, and also the cadence, because each senator only gets five minutes, so you'll be like halfway through an answer. And then it's like, beep, time's up. You know, next. And so, they got me used to the somewhat stilted way that the questioning goes in rounds like that. So, I felt very well prepared. By the time the actual confirmation hearing came around, we had done several dry runs.

John Reed: [00:28:57] You see on the news when there's a nominee for an agency position that they're walking around the Senate, meeting with senators in their offices. Was that part of your preparation, too?

Karla Gilbride: [00:29:07] It was, so both before and after the hearing, I had several one-on-one meetings with senators and with senators' staffers. So, it was an interesting experience. I mean, it really ran the gamut of the sorts of things that they asked about. Many of them just wanted to hear about me and my background and my priorities, or things I wanted to work on. Some of them had very specific things that they were interested in, that they had heard about from their constituents.

What are you going to do about the janitors and their pay, and, you know, just very specific questions that they wanted to know that I would take on and make a priority if I was confirmed.

John Reed: [00:29:44] Or that they could use as a soundbite with their constituents back home, right?

Karla Gilbride: [00:29:49] Well, definitely the confirmation hearing part. I mean, in the public hearing, there are certain things that do feel like they're sort of prepackaged for cable news or for making a video. It's a strange process in that way because sometimes you feel like you're having a real conversation, and sometimes it just feels like people are making speeches.

John Reed: [00:30:09] What were the tougher questions? What did people want to know in particular that was difficult?

Karla Gilbride: [00:30:14] There were questions about things that the EEOC had done in the past that maybe that senator didn't agree with, and would I do the same thing, or would I change the practice? So, some of them were policy questions. Some of them had to do with what would happen—and this turned out to be prescient for what did happen—but would I stay on if I was appointed by a Democratic president, by President Biden, what would I do if a Republican were elected? Would I step down? So those sorts of questions. And then some that were focused on Big Government or the Deep State. So again, not really so much anything specific to me, but that this agency that I was going to go work for, or being asked to head up, has done things to regulate small businesses that are harmful, and what's my position on that?

John Reed: [00:31:09] The performative part of the hearing, right?

Karla Gilbride: [00:31:11] Right. Those were not necessarily questions that I felt— it didn't really matter what my answer was, because it was more for them to ask the question and get their talking points on the record.

John Reed: [00:31:21] You coming from the outside to take on this very, very important role with the EEOC. Is it unusual in the sense that somebody didn't come up through the ranks? What's the history there?

Karla Gilbride: [00:31:31] So it's gone both ways. There have been people who've come in from the outside. People who've come in from big law firms. There are other general counsels who had more of a similar background to me in terms of doing plaintiff's work. But then yes, there definitely have been general counsels who came up through the ranks within the agency, and coming from the outside where I didn't know anybody and nobody there knew me, it definitely was a, a learning curve and an adjustment period just to get to know everyone and get up to speed with all of the acronyms and the way that the government works, which was a challenge compared to somebody who had come up from within who would already know all of those things.

I also think that coming from the outside maybe gave me some fresh perspective and just a different insight into looking at the agency with, I guess, what they sometimes will call beginner brain, right? Because I'm not steeped in ‘this is the way we do things.’ So I can ask questions. Well, why is this the way we do things? Why don't we do this a different way? But certainly, the learning curve was steep, and I had to try to climb it as quickly as I could because I didn't know how long I was going to be there.

John Reed: [00:32:41] Apart from the acronyms and the government-speak and getting to know people, you knew the law; what else did you have to learn to be effective in that role? You had far more reports than you've ever had before. Was that part of it becoming a manager, a manager of more people? I'm curious as to how you moved into the role to become effective.

Karla Gilbride: [00:33:03] Well, definitely the size. Public Justice was a small nonprofit, and I moved from there to an agency where the legal staff alone was several hundred people. Getting up to speed entailed beyond just getting to know people and getting to know what the processes are, was just understanding how the different offices, the different regions of the country, the field programs, which is the investigators and the administrative judges and the mediators. There are people who interface with the state and local agency partners that the EEOC works with, and also the tribal employment rights organizations for Native American tribes. All of those people interact and that comes together to be greater than the sum of its parts.

I could learn a bit of it from being in D.C. at the national headquarters, but I also traveled to all 15 of our district offices around the country and met with the staff on the ground, um, and I feel like that's where I really got to see how all of the different pieces of the puzzle fit together.

John Reed: [00:34:07] A new administration can bring change, and, boy, has it. So, President Biden left office. What happened to your role at the EEOC?

Karla Gilbride: [00:34:16] So I had been wondering what would happen, and I met with the transition team in, I can't remember whether it was January, late December, early January, something like that. I thought that it was certainly possible that I would be asked to leave. And I got an email late at night on January 27th from someone in the White House Personnel Office basically telling me that my services were no longer required. So basically, one week into President Trump's second term, I was terminated.

And what was remarkable about that situation was at that point, four of the five commissioner spots were occupied. Commissioner Sonderling's term had ended in 2024. That vacancy hadn't been filled, so there were only four commissioners, three of whom were appointed by Democratic presidents, one of whom was appointed by President Trump in his first term. And two of the three Democratic appointees were terminated at the same time that I was, and that was unprecedented.

You need three commissioners to constitute a quorum, and then there were only two. So, that sort of overshadowed my being terminated because that had happened before with general counsels, but it had never happened that a commissioner was removed from their position before the end of their term.

And Vice Chair Jocelyn Samuels, who is one of the two commissioners who was terminated, she has filed suit, and that case is ongoing. Whether it was legal for her to be fired is subject of litigation right now. But in my case, because there was a precedent for it, and it wasn't really unexpected on my part. I was already thinking about what was going to be my next move if that did happen. And so, I was ready to turn the page and start a new chapter.

John Reed: [00:36:08] Tell us about that new chapter.

Karla Gilbride: [00:36:10] So I am currently working as the deputy director of the Public Citizen Litigation Group. Public Citizen is a public interest organization that has largely worked on consumer and public health and safety issues over the years. It's been around for over 50 years, and the litigation group has done a lot of work on government accountability and government transparency, as well as corporate overreach. And so, it seemed like a good home for me with my public interest law background. And especially given some of the things that are going on with the current administration, I wanted to be at a place on the front lines of making sure that the government doesn't abuse its power.

Because to my theme from earlier about people abusing their power or something, that makes me very angry, and that makes me want to push back. I see a lot of that happening right now with this administration, and so Public Citizen is a great place to be standing up for the rule of law, and that's what I'm trying to do.

John Reed: [00:37:14] At Public Justice, the focus for you was on appellate work. Is that what you're doing at Public Citizen?

Karla Gilbride: [00:37:20] Not right now. I imagine that there will be more of that in the coming months. But since we are filing a lot of new cases and filing motions for preliminary injunctions, trying to stop agencies from being shut down, stop things that we think are unlawful agency actions, we're in the district court a lot, and we are often filing things that have a very short timeline. So, it's not necessarily what I'm most comfortable with, but it's what the situation calls for. So, I've been writing a lot of briefs at 10:00 and 11:00 PM in the last few months.

John Reed: [00:37:59] A question I ask pretty much every guest is, what do you consider to be your greatest hits? Those matters of which you're particularly proud? It wouldn't surprise me if you mentioned the cases that we talked about before, but I'm curious if you have others to share.

Karla Gilbride: [00:38:13] Well, another case that I'm really proud of, it is not an appellate case. It's actually one of my few things that I did at the trial court. I had a bench trial in a case involving migrant farm workers who were brought to harvest lettuce in Arizona and California from Mexico. And they were also required to sign these arbitration agreements, giving up rights to go to court and giving up rights to band together with their colleagues. So similarly to Robin Morgan's case, they wanted to challenge some of the working conditions that they experienced. And the employer said, “You can't because you signed these arbitration agreements.”

We looked at the California contract law. This is a contract that they signed. No question about whether they signed it or not. What are the defenses to a contract not being enforceable? And one of the ones that rarely gets used, but it does exist in the law in California, is economic duress. So, when the bargaining power is so unequal between employer and employee or between the two parties for the contract, in this case, employer and employee, you can make an argument that you are under economic duress.

We made that argument in this case, and then we wound up having a trial because under the Federal Arbitration Act, you can get either a bench trial or a jury trial, and we asked for a bench trial, and we had live testimony. Our client testified, some of his coworkers testified about the conditions they were working in at the time. The company put on witnesses. After two days of live testimony, the judge ruled and went through the factors, and said that this was an example of economic duress.

Both because it was a novel application of law really, something that I don't think had been done ever or not very often, to argue this in an arbitration case, but also just the opportunity for our farm worker client to testify and tell his story in a court and to be believed—that was one of the things he said, the fact that they believed me, they listened to me talk about power imbalance—and he had a chance to speak his truth and be heard.

Ultimately, that decision was reversed by the Ninth Circuit, I need to say for the record. So, it's no longer binding law in California. But I think it was a really just powerful moment of what lawyering can be. Because I think we made new law, we kind of changed the rubric or the limits of how the law could be used for low-wage workers. And there was just a very visceral opportunity for the worker, for his words to have as much weight as the employer's words, and for the court to make the ultimate decision of what had happened here, and whether what had happened was a violation of California law. So that was a really neat experience and kind of made me want to do more trial work.

John Reed: [00:41:02] I think of that plaintiff, that client. You may not have known it when you were your younger self, but that was the client you always wanted to represent for that very reason. You know, that was the little guy. That was the underdog.

Karla Gilbride: [00:41:13] Absolutely, and it was a really special experience. I spent several days working with him, preparing him to testify, explaining what the process was going to be like. I got to meet some of his family. We stayed in touch afterwards and, just also the co-counsel that I worked with at California Rural Legal Assistance who do legal aid work and work with these communities all the time. They're also really, really great lawyers and really great people.

So, yeah, I think you're right. It was kind of a dream come true for me to do that work and to continue to speak truth to power and to use the law. Because it's a really powerful tool, and I love being able to use it to make things more fair and more balanced.

John Reed: [00:41:58] So I'm going to ask this out of order. I'm interested to know your experience as a blind person in law school. It is an incredibly reading-intense education. You can answer this any way you want, but I'm curious if there's any particular stories or accommodations or whatever that would help somebody sighted understand your particular journey through law school.

Karla Gilbride: [00:42:22] So you're right that it is very reading-intensive. For the most part, I read by listening. And so, I do use braille for certain things, and the types of things that I will use braille for is when I am going to be speaking and want to have access to information at the same time that I'm speaking. For example, if I'm questioning a witness or if I am doing an oral argument where I want to have case names and citations in front of me, then I will use braille for having quick access to that information.

But for the most part, when I'm just reading cases or reading briefs, I have a screen reader program, which comes built into any computer. So, you just install it as a piece of software, and then it makes the computer read out loud, whatever's on the screen. And so that was also in law school, how I accessed my textbooks. So, I would have a digital version of the textbook and a PDF file, and then I would have the screen reader on my computer read it out loud to me. Same thing with like accessing Westlaw or Lexis to read cases, and there was a bit of a learning curve for that. Any sort of new web interface, just getting conversant with it.

But I'm pretty lucky, I think. I went to law school in the early 2000s, and we had pretty much already made that digital transition. I think blind people who were going to law school earlier than me had to do a lot more with human readers accessing printed materials. But by the time I was in law school, we were really using computers to do all of those things already.

I think people who can dictate in full sentences, full paragraphs, I think that would be incredibly helpful practice for oral argument, to be able to speak so fluently. But it's not something I've ever had to do because I've always written my answers for exams and for briefs and things using the computer.

John Reed: [00:44:21] As we've been talking, a couple times in the background, I've heard a very, very fast voice. Is that a reader that's reading messages on your phone to you?

Karla Gilbride: [00:44:31] Yes. So, I have the same sort of screen reader that I was describing for the computer; I have a similar program on my cell phone, and so that does the same function. It just reads out your text messages, or your emails, or whatever is coming through on the phone. I have a lot of robotic voices talking to me all day long.

John Reed: [00:44:53] That robotic voice that I heard in the background, it was very fast. Is your hearing that much more acute, that you can hear things, I guess, more quickly, if that's the right term?

Karla Gilbride: [00:45:03] I think you train it up. So, I don't think my hearing is more acute, but I do, because I take in so much information through that modality of having things read out loud to me. The faster you can process it, the more you can read. So, I've certainly trained myself to be able to speed read, I guess you would call it. And depending on how much I have to read, I'll even sometimes jack it up even faster just to get through something.

John Reed: [00:45:31] This has been a real honor for me in so many different ways. The Supreme Court stories, your EEOC career, your public interest career, as well as your lived experience, and I thank you so much for taking the time to share it with me.

Karla Gilbride: [00:45:43] Thank you so much. This has been a lot of fun.

John Reed: [00:45:47] And to you listening, if you enjoyed this conversation, I'd really appreciate it if you would please subscribe to Sticky Lawyers wherever you listen to podcasts. It helps make sure you don't miss future episodes. And if you have a minute, leaving a rating or review really does help other people, lawyers and lay people alike, discover the show. Even just a few words about what you found interesting or useful makes a difference.

Until next time. I'm John Reed, and you've been listening to Sticky Lawyers.

Deputy Director of Litigation, Public Citizen

Karla Gilbride is Deputy Director of Public Citizen’s Litigation Group and a former general counsel at the EEOC, where she led the agency's litigation and amicus program to combat discrimination in the workplace. She previously co-directed Public Justice’s Access to Justice Project and secured the U.S. Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Morgan v. Sundance, advancing fairness in contract enforcement for workers and consumers. Drawing on her lived experience as a blind person, she continues to be a champion of civil rights and accessibility.