From Law School to the Bankruptcy Courts to Clown University

Just in time for Thanksgiving, meet Charles "Chuck" Tatelbaum, an octogenarian attorney who has built an extraordinary 59-year legal career by recognizing opportunities and going all in.

When Congress enacted the new Bankruptcy Code in 1978, Chuck was ready to take the new laws and rules and run with them. When the chance arose to help post-communist countries draft their first-ever business laws, he got on a plane. And when he sees ways to give back—to the profession, to his South Florida neighbors, and at a certain parade this time of year in New York City—he steps up.

Listen in as Chuck talks about his remarkable legal career, misconceptions about bankruptcy law, notable cases, outreach efforts that took him abroad, and his commitment to pro bono work, public television, and the local immigrant community. It's not all serious, though; there's time for some clowning around, too.

Guest Insights

- [00:02:34] How Chuck became a certified Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade clown.

- [00:05:55] Getting physically and mentally prepared for the big day.

- [00:08:39] Chuck's clown portfolio, from toast to birthday cake.

- [00:15:11] The introduction of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code in 1979.

- [00:18:29] Founding and supporting the American Bankruptcy Institute.

- [00:25:13] Helping Croatia and Slovakia draft their first business and bankruptcy laws.

- [00:27:39] Notable cases: From Chevrolet's largest dealer to Turkish superhighways.

- [00:37:31] Chuck's commitment to public TV, the community, and pro bono work.

Links From This Episode

02:34 - How Chuck became a certified Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade clown.

05:55 - Getting physically and mentally prepared for the big day.

08:39 - Chuck's clown portfolio, from toast to birthday cake.

15:11 - The introduction of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code in 1979.

18:29 - Founding and supporting the American Bankruptcy Institute.

25:13 - Helping Croatia and Slovakia draft their first business and bankruptcy laws.

27:39 - Notable cases: From Chevrolet's largest dealer to Turkish superhighways.

37:31 - Chuck's commitment to public TV, the community, and pro bono work.

John Reed: [00:00:08] Sometimes the stars align, and this episode proves it in more ways than one.

When opportunity knocks. A sticky lawyer not only answers the door, they welcome it in, offer it a drink, and suggest they move into the room above the garage. If that meaningful opportunity comes along, the sticky lawyer goes all in, even if the payoff won't pay off for a while.

Take today's guest, for example. Seldom does an entire area of law undergo a complete transformation, and you're there to run with it. Rarely would you have the vision to launch an organization that will one day have thousands of members in the U.S. and abroad. Never would you think you might help other countries after the fall of communism, draft new business and commercial laws, and train lawyers and judges in those new laws. And hardly would you find ways to give back and give back big to not one, but several communities.

When opportunity knocks, the stars align. The only questions a sticky lawyer asks are, where have you been all this time, and when do we get started?

For 59 years, Charles Tatelbaum has had a reputation as one of the country's foremost bankruptcy, creditors' rights, and complex business litigation lawyers. A director at Trip Scott in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, he also chairs the firm's creditors' rights and bankruptcy practice group. Chuck represents various Fortune 150 companies, and his name is on several landmark bankruptcy cases. As you'll also hear, he's a selfless nonprofit leader and volunteer.

The stars aligned for me, too, with this episode. Because of Chuck's special connection to Thanksgiving, he's the perfect guest for today's show.

Welcome to the podcast, Chuck.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:01:51] Wonderful. I'm so happy and excited to be part of it.

John Reed: [00:01:54] Chuck, I have to ask, you've been practicing as long as I've been alive. You've built an incredibly distinguished career. Why not hang it up? What keeps you going?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:02:03] I still enjoy what I do, and I'm helping people, I hope. I think I do, and I really enjoy it, so I'm not sure what else I would do that would be so worthwhile.

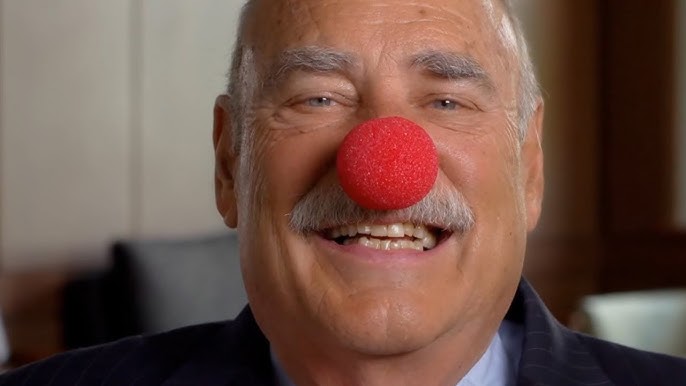

John Reed: [00:02:16] There's no better answer. We're going to talk lots about your practice, but before that, given that it's the week of Thanksgiving, I'm very interested to learn about your volunteer involvement with an annual American tradition, the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade. And I think I can say this without offending, Chuck, you're a clown.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:02:34] I am, and proud to be one.

John Reed: [00:02:36] Well, take it from the top. How did this all start?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:02:39] Well, I've been fortunate to represent Macy's and its affiliates for 30 years or so. About 15 years ago, I was in New York following a hearing for one of their cases, and I was having dinner with one of my friends who's on the legal staff. And having been in the drama club in high school and played in the band through high school and college and afterwards, I like to perform, so I just sort of casually said to him, “Do you know how to get into the parade?”

And he looked at me, and he sort of smiled, and he says, "Yeah, I am Macy's clownsel. One of the assignments that I have is for the Macy's Entertainment Group, which is the 4th of July fireworks, the parade, and other things." And so, then he went on to explain that you have to be affiliated with Macy's and be sponsored, and he would sponsor me, and that I would have to go to an accredited clown school in order to get certified. So that eliminates some liability potential for Macy's. And then if I passed a test, I could get into the parade.

So, without telling my wife, I signed us both up. And we went to Clown University, which is part of the Big Apple Circus in New York, took the training course, passed, and 13 years ago participated in the first parade.

John Reed: [00:04:06] You're in Florida. Were you in Florida at the time?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:04:09] Yes.

John Reed: [00:04:09] Was there not another clown school closer to you, or that's the one they wanted you to go to?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:04:14] Well, they had an arrangement with the Big Apple Circus. The Big Apple Circus trained most of their parade clowns, so although more costly, certainly easier to, and more easy to do it.

John Reed: [00:04:26] And what goes into a Clown University training?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:04:30] Well, we're not going to join the circus. They made that very clear. It is to teach us how to make facial expressions that are funny. How to make clown noises. How to do gyrations that are funny. What not to do. How not to scare children. Things about makeup if we do our own. Just general things of how you clown the right way in order to make people happy and not do anything that's wrong.

John Reed: [00:05:00] And be a fun clown as opposed to one of those scary clowns.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:05:03] Absolutely.

John Reed: [00:05:04] You mentioned that to avoid risk, Macy's required you to go to an accredited clown school. Why would that be?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:05:12] In the parade, we are representatives of Macy's, and they want to make sure that you act accordingly because in this day of litigious everything, as I know from representing Macy's, they want to make sure that everybody is properly trained before you go into the parade. And then each year, we have to sign a clown oath, which lists all the things that we will do and will not do.

John Reed: [00:05:39] And all this is on your own dime. You're going to training, you're traveling back and forth.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:05:44] Well worth it.

John Reed: [00:05:45] Let's say it's September before a Thanksgiving parade. What's your timetable for preparing and training, and getting ready to do your thing?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:05:55] Well, I started a regimen as a result of my being in the parade. I walk and jog every morning between 5:30 and 6:30. And being in Florida, it's easy to do 12 months a year except when it's raining. But beginning Labor Day, which is my start date, that's when I'm walking, and I spend the time walking through the neighborhood, waving my arm, in order to build up the arm muscles.

Because when you're waving for multiple miles, most of us don't have those muscle things. And then towards the end, I will sometimes wear a nose in order to practice breathing through my mouth in the event that the costume requires wearing a nose.

John Reed: [00:06:38] I hope your neighbors know what you're doing and you're not just that crazy guy that's waving and wearing a clown nose.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:06:44] Most do, but we have the Fort Lauderdale police do a private patrol through our neighborhood. And all the patrol officers do know who I am, so that when they see me walking, waving, and looking crazy, they just wave and smile.

John Reed: [00:07:02] The police only know you because of your clown role, I trust.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:07:06] I hope so, yes.

John Reed: [00:07:07] Okay. Very good. That's your local Florida training. Do you just show up on Thanksgiving morning for the parade?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:07:15] No. You go up a couple weeks before to get renewed training and learn what your costume is, meet with your clown captain, and depending on which costume you're in, your clown captain may go over up to three dance routines that the group would do in the event that the parade stops for a commercial or something. Meet the people who are with you, and just get used to what your clown captain expects of you in the group. Because different costumes require different actions during the parade.

Our regimen is to go up on Sunday before Thanksgiving, so I can walk in New York, where it's cold. Also, little things. New York streets are different in that the center of the street is built up higher than the curb area for drainage. And since we walk along the side, you actually tilt a little bit. So, I walk in the gutters in New York, because I like to walk on the left side to build up my muscles, because one's going to be more than the other.

John Reed: [00:08:21] I never imagined there would be so much thought that would go into the training. This is fascinating. Now, I've done my research. There are Alphabet Clowns, Artist Clowns, Birthday Party Clowns, Keystone Cops and Robbers, Nutty Cracker Ballet Clowns, and Spacey Clowns. Which have you been, and what has been your favorite?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:08:39] Well, there've been others than that. I've been a Celebration Clown. I've been a Raggedy Andy Clown. I have been a Football Player Clown, and I have been a Keystone Cop Clown. Oh, and the first one was a Breakfast Clown where I was a five-foot piece of toast behind the Pillsbury Doughboy balloon, and my wife was a stick of butter.

John Reed: [00:09:02] What has your favorite clown or clown costume been?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:09:05] I think it's been the birthday cake. Because the dance. When we were called to the center, there were six slices of cake and 12 ice cream cones. And so, the six of us who were slices of cake came together into one round cake and then did a dance as a cake.

John Reed: [00:09:23] I'm so loving this. And then, do you interact with the crowd, too?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:09:27] Yes, on that one, what we did is we would go over to one side of the street or the other where there were the most kids, and yell out, "Who's having a birthday?" And if there was someone, we would sing to them. And if not, we'd say, “Well, it's your birthday,” to some seven, 6-year-old, get their name. And we would sing to them and throw confetti at them.

John Reed:[00:09:47] Now, this clown gig is no joke, and, as you talked about with the insurance, Macy's takes it very seriously, including evaluating you as a clown. Can you talk about that?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:09:58] We have been told that three different places during the parade were videotaped to make sure we are animated enough and doing what they would expect us to be as our clowns. And of course, our clown captains evaluate us as well. It is very important to them. It's just not something that you walk around. You need to be yelling Happy Thanksgiving. You need to be interacting with the people on the side of the street. They make it very clear we're not there to be on television. In the 10 years that I've done it, I've only been on TV once for a microsecond because when we pass by the reviewing stand, it's between a float, a band, a performer, or a balloon. So, they really rarely show the clowns. Our job is to entertain the three, three and a half million people that are lining the street.

John Reed: [00:10:51] And how long is the parade route again?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:10:53] It depends on where you start, but it can be anywhere from two and a half to three and a half miles.

John Reed: [00:10:59] Take me to the day of. What time are you getting to your required area, and what is the day of preparation?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:11:06] Okay. We arrive at the Hotel New Yorker, which is at 34th and Eighth, between 4:30 and 5:00. They then have to check IDs. I mean, they're very, very security-conscious. We go into a massive room where there are racks of clown costumes, depending on what costume you're wearing. Each group has two costumers there. There is your costume in your size with your name on it, hanging. The costumer helps you get into the costume, and you leave your civilian clothes there.

Then you go to the next room, which is the makeup room, where you wait in line. They have about 40 makeup artists, and they call you as one becomes available. You tell the artist what clown you are. They look on a chart to see what makeup you get. You then get your makeup. If you're a Birthday Clown wearing a big foam rubber cake, that can be difficult because you have to go down a long flight of steps, out onto the street, and into buses also. Navigating on a bus with a piece of toast that's five feet across, or a cake, is a little bit cumbersome.

They then take us uptown to Columbus and somewhere around 74th. We walk through the balloon inflation area and we're given stations as to where you are in the parade and we stand in Central Park West for anywhere from 6:30 on until 9, 9:15, 9:30, up to 10:30, when at that point they are melding into the parade the floats, the balloons, the bands, the performers all staged in different areas and they just meld right in. It's a very efficient system.

John Reed: [00:12:56] You know, I would've thought you were all in one place, and they just say, go, and you go. But no, they have to, as you say, stage in all these different places.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:13:03] It's also very interesting because the floats are built in New Jersey, and every float is on hinges, and they have to fold them down to get through the Lincoln Tunnel at midnight. And then they reconstruct them again. And the other thing they have to do is every traffic light and street light pole in New York that's on the parade route is on a hinge, so the balloons don't hit them.

John Reed: [00:13:28] I had no idea. It's not a cakewalk. I couldn't resist it. Sorry for the pun.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:13:33] And we're not clowning around.

John Reed: [00:13:35] And we're not clowning around. Now, you get to choose your clown outfit, or is it assigned to you?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:13:41] It is assigned.

John Reed: [00:13:43] So there's no seniority. After so many years, you get to choose?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:13:46] Nope, it's a surprise and you just enjoy it, whatever it is.

John Reed: [00:13:51] Of course, I have to ask. Mother Nature plays a part not only in the weather, but also with one's body during the parade. How does that work?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:14:00] Well, most people use a product that protects them while they're in the parade. They have a big sign in the dressing area: Coffee is not your friend. Part of our clown oath is, once we have gotten in the costume, we can't eat or drink anyway. So, I limit my fluids from six o'clock the night before.

John Reed: [00:14:23] That makes very good sense. Unfortunately, you're not participating this year. Are you planning to get back there?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:14:30] It's not voluntary that I'm not participating. You need a sponsor, and senior-level people all get one person to sponsor. My sponsors have all retired, so I'm trying to find another one, but next year is going to be the 100th anniversary, and I'm pulling all the connections I have with Macy's to find a sponsor for next year to do the 100th.

John Reed: [00:14:53] Well, I hope amongst our thousands and thousands of listeners to this podcast, somebody can put in a good word for you and get you back in the program. That would be great.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:15:01] Wonderful. Thank you. It's very exciting.

John Reed: [00:15:03] It is, and I'm so thankful to you for sharing this.

Okay. Enough fun. Fun's over. Let's talk about bankruptcy and insolvency law.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:15:11] My favorite.

John Reed: [00:15:11] What's the biggest change that you've seen in bankruptcy law and the bankruptcy practice over your career?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:15:19] There was a momentous monster change in 1979. Prior to 1979, we had the Bankruptcy Act, which actually went back to the 1800s and wasn't even substantially changed after the Depression. Congress decided to pass a new bankruptcy code, which it did in 1978, which became effective in 1979. And it dramatically changed bankruptcy law in this country, even to the point where what we all know is Chapter 11 now was virtually non-existent under the Bankruptcy Act. So, it just totally changed everything we knew about both substance and procedure. We never had bankruptcy rules before. And then the Supreme Court had to promulgate bankruptcy rules to go along with the new bankruptcy code.

John Reed: [00:16:14] What was the impetus? I mean, obviously, the world had changed over those many decades, but was there something in particular that prompted this overhaul?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:16:23] Well, I think it was more of globalization, but more my view is the Uniform Commercial Code. Because before 1954, every state had its own laws with respect to sales, liens, everything that the UCC covers. All of a sudden, you had more interstate commerce like you didn't before, and banking regulations changed so that there was a need, and companies were bigger, conglomerates were created. There was no vehicle for reorganizations. The need for Chapter 11, also for Chapter 13, for consumers, Chapter 9 for municipalities. All of those came together.

John Reed: [00:17:11] And it sounds like this elevated the bankruptcy practice, made it more, for lack of a better word, sophisticated.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:17:18] It did, because before it was virtually all just liquidation. And it became much more sophisticated. It required a lot of learning. It's not as complicated as the Internal Revenue Code, but think of taking everything you knew about the law, and there is a new code that is changing everything and then new rules to go along with it.

And it was mostly younger practitioners willing to do it, and it created a whole new level of sophistication within the bankruptcy bar. And the bankruptcy judges, some of the old referees, decided to retire at that point. And we got a whole new bevy of people on the bench that really knew this stuff or were certainly more academically oriented.

John Reed: [00:18:09] So it sounds like you were in the right place at the right time in your career, taking on this momentous task of learning this new code.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:18:16] Yes, I was in the right place at the right time, and the people I got to know through the American Bankruptcy Institute, which was formed around then, we were all pretty much age contemporaries.

John Reed: [00:18:29] Let's talk about the American Bankruptcy Institute. You're giving yourself short shrift. You are a founding member, and for those listening who may not be familiar, ABI is the largest multidisciplinary nonpartisan organization in the U.S. that's dedicated to virtually all matters related to insolvency. In fact, it's not just lawyers. There are accountants, and financial advisors, and others. What prompted you and your co-founders to organize this?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:18:55] Before that, there was, and there still is, an organization called the Commercial Law League of America, which dealt with bankruptcy and collections, and it was sort of the only place that had a discipline. There were a couple of lawyers who worked on the Senate and House Judiciary Committees on the Bankruptcy Code who reached out to a group of us and said, you know, we need to form an organization because we have no organization for this new thing. So, the ABI was formed. They hired an executive director. A one and a half room office. There were, I guess, 10 of us on the board or so, and we got it started.

John Reed: [00:19:40] And it is 10,000 members today, so that's exponential growth. It's not just a club. It's not just a bunch of people who do the same thing, maybe from different disciplines. It's got an educational purpose. There's other things that it offers. Is that a fair statement?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:19:53] Oh, absolutely. We have the American Bankruptcy Institute Law Review, which is a whole law review that's now done in conjunction with the National Association of Bankruptcy Judges. We have symposia all over the country. We have a whole international law division. There's a monthly publication that's scholarly. Daily, a thing comes out telling you what case is most significant. Maybe a hundred different book publications. It is interdisciplinary. Huge staff and excellent meetings throughout the year, two nationals and regionals geographically.

John Reed: [00:20:34] There were some doubts there in year one and two whether it was going to last. Is that accurate?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:20:39] Very accurate. We ran into a cash crunch, and all of us agreed, and we lent money to the ABI at the time with no real expectation of being repaid. We were, thank goodness, but we actually had to fund it ourselves to keep it going because it was just getting started, and there were expenses.

John Reed: [00:21:03] We're going to talk about how prolific you are in terms of writing and speaking and things like that, but I gather that you have been part of that ABI educational mission from day one. You weren't just a member of the board of directors, you had other roles, too.?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:21:17] Because I was practicing in Baltimore and the ABI was in Washington, I was closest in proximity. For six years, I was the editor of what is now the ABI Journal. It was called the ABI Newsletter. And of course, we didn't have internet, so I would either drive or take the train to Washington once a month and take the copy to the office. I was vice president of research for two years. Various other specific roles developing it.

The other thing it founded is the American Board of Certification, which certifies both consumer bankruptcy lawyers, business bankruptcy lawyers, and commercial debt lawyers. And I was on the board to found that, and I was on the founding board of the Law Review as well.

John Reed: [00:22:07] For every bankruptcy attorney I've ever met, at some point, they said, “Oh, I'm going to an ABI conference. I'm going to an ABI event.” It's just a fixture in their practices.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:22:16] It's because at the event, if you are a consumer-debtor bankruptcy, there's CLE for you. If you're representing banks on private lending deals, there's seminars for you. The networking is important. It isn't networking so much as getting business, which is a factor. It's a networking you learn, but you also get a confidence that when you have a case in another city, you know the people. And that's a confidence of working together because bankruptcy is more collaborative than it is litigious.

John Reed: [00:22:53] I don't think it's an exaggeration to say that you are if not the go-to bankruptcy practitioner, certainly a go-to bankruptcy practitioner, not only for your representation, but also for the breadth and the depth of your knowledge.

So, I'm going to dust off my law school cobwebs here. We talked about Chapter 7, that's liquidation, eliminating most unsecured debt. There's Chapter 11, which for a corporation, a company would be in reorganization while continuing to operate. You mentioned Chapter 9, municipal bankruptcy. We've got some experience with that here in the Detroit area. One thing I didn't know, though, was Chapter 15.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:23:31] Chapter 15, which came later, is the international ancillary proceeding where you have international bankruptcies, where the main bankruptcy is in a foreign country, and based on the principle of comity and some of the treaties we have. Where there are assets located in the U.S., they can be administered in a Chapter 15. Unlike the other chapters where you file and the court takes jurisdiction, in Chapter 15, there has to be a threshold determination by the court, what's called recognition, that it applies. And then if that's the case, Chapter 15 is administered.

Chapter 12, which came later, is for what are called family farmers. You don't necessarily have to be a family farmer, but the need for a separate reorganization for farmers is very important because their business is so different than any other mercantile business that the farm chapter is needed.

John Reed: [00:24:35] Tragically, that's a very busy bankruptcy court that's handling Chapter 12s these days.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:24:41] iI is, and admittedly so, it is much more debtor-friendly because the farmers are less sophisticated. They have less wiggle room in running their business. They don't have control over commodity prices or the weather or other things. So, it's much more debtor-oriented in order to save the family farms.

John Reed: [00:25:05] Now, this Chapter 15 foreign bankruptcy work, that led to some other international work. Can you tell us about that?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:25:13] As a result of my friendships with people in Washington, one of the staff attorneys for Senator DeConcini of Arizona, who was the lead senator on the Bankruptcy Code revision, asked me and others to take a leave of absence and work for USAID, former USAID, I guess, as part of the State Department.

When communism fell in the Eastern European countries, those countries had no business laws. Everything was the state. They never had a thing called a mortgage, a security interest, or contracts of sale or anything. We led or worked with teams of professors, judges from all over the world who would come in, and we helped them create their bankruptcy laws. I had the pleasure of working in both Croatia and Slovakia.

John Reed: [00:26:07] It would seem with something like that, it's not training the current bar of lawyers. Is there more of an emphasis at the law school, at the university level?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:26:16] We worked, actually, with the professors, the lawyers, and with the Supreme Court. I remember sessions with the nine members of the Croatian Supreme Court, and one of us, I think it was me, said the word "mortgage." And the hand went up. And half of them had headphones on because we had to have the simultaneous translation. And the question was, what is a mortgage? I've never heard that term before. There was a lot of education both at the academic, the judiciary, the legislative, and the bar.

John Reed: [00:26:51] How long was this process? How much time did this take?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:26:54] It was a process of a year for each of the countries, off and on.

John Reed: [00:26:58] And you were maintaining your practice at the same time.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:27:00] I was really on a leave of absence. There was no internet or anything like that, and FedEx really wasn't there, so my firm was very accommodating. And I loved it. It was not financially rewarding at all. But it was a highlight of my career, I would say.

John Reed: [00:27:19] Oh, I can only imagine how consequential your work was.

I'll ask you this, Chuck. Tell us about not only your notable cases, but—and maybe they overlap some of the cases or matters of which you're most proud, that had personal meaning to you, regardless of the outcome.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:27:39] I think one of them, and I'll talk about what's public, in 2008, the largest Chevrolet dealer in the country filed Chapter 11. It was called Bill Heard, filed in Alabama, rural Alabama, one of the places they were headquartered.

Bill Heard had 14 dealerships. They accounted for 7% of all the Chevrolet sales in the country. I represented what had been called GMAC, Ally Financial, that had hundreds of millions of dollars outstanding. And working with other secured creditors, the debtor's attorney, and others, we effected sales of ten of the 14 stores, and did everything to the point that every lender was paid in full with interest whose liens weren't avoided. There were some bad liens there. The judge actually, because I sort of led the group of lenders, 'cause mine was the biggest, because we had lent to ten of the 14 stores, awarded my client a $300,000, what's called a Substantial Contribution Bonus.

So that one. The other one was a company called Dillingham Construction, which was a Chapter 11 in Oakland, California. Again, it was Ally Financial. It was a worldwide construction company that had gone in 11, and Ally had as collateral a 50% joint venture interest in building the largest superhighway in Turkish history. We also had $60 million of letters of credit up to guarantee the performance bond. And it literally took me nine years and 27 trips to Turkey to work with the bankers, the joint venture partner that was Turkish, and others, in order to get the highway completed, to get our collateral released, get all of our money back, and we got paid interest and attorney's fees and paid in full on that one as well. And I loved it because I got to deal with and meet some wonderful people in the Turkish business community.

John Reed: [00:30:03] Chuck, these stories that you're telling me. I think there's a misconception out there when you talk about corporate bankruptcy that it's cold, that it's just a series of transactions. Who's going to get paid? Who owes money? Jobs are at stake. The people part is sometimes lost. What do you think is the biggest misconception about the type of bankruptcy work you do amongst the public? Perhaps the lay public?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:30:26] That it's not, as you say, cut and dry. One of the things I love about it is each case is different, and you have to learn a new business. Without giving anything away that is private. I'm dealing with a very large chicken and fertile egg business now that got hit with the hurricane and some other things, where we have 1.8 million eggs in the incubation right now. And selling 600,000 chickens in the broiler business a week, and we're dealing with farmers and feed mills and everything all over the country.

So, you have to learn the business, learn the intricacies of the business very quickly, whether you're representing the lender or the debtor or the unsecured creditors, because everybody has to work together. And then you have to look at all the people who are the creditors, the employers, the employees, and everything, because all these people have to work together to get to the end. And so, it's not just something that's plain and simple; that's the same for every case.

John Reed: [00:31:39] Apart from formal bankruptcy actions and proceedings, what else does your practice entail? I think there's, again, another misconception that bankruptcy is only going to court and resolving issues within that formal framework.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:31:56] I would say if I'm successful, and most of us in our practice are, 70% of the cases never go to bankruptcy. Because when there's financial distress, they work on them, and they do an out-of-court resolution. That is the goal.

Bankruptcy is sort of like the last resort. It's much better to do it out of court. It saves money. It does a lot of things for people, and that's what our goal is. But the other thing is, is bankruptcy spawns a lot of complex litigation, and very interestingly, which a lot of people don't know, many of us in the bankruptcy court, outside of the bankruptcy court, but in derivative cases, wind up trying complicated jury cases involving financial issues. These are six, eight-week jury trials where you have to go to a jury and have them understand the complex financial issues in order to resolve them.

John Reed: [00:32:55] And your bankruptcy practice is a hundred percent federal courts. Are you ever doing any state court work?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:33:02] Not if I can help it, but uh, yes.

John Reed: [00:33:06] Okay.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:33:07] The Bankruptcy Code and the bankruptcy rules and Title 28 of the U.S. Code dealing with courts allows removal to the bankruptcy court for a lot of things. But every now and then, we are in state court somewhere in the country, and that can be a challenge.

John Reed: [00:33:24] I mentioned earlier, I'm quite struck by your ongoing willingness over all this time to help educate people about bankruptcy and insolvency law. As I said, you're a prolific author dating back to and before your ABI Journal editor role. You've also become kind of a go-to resource for the media. What's the backstory there?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:33:46] Early backstory is when I first started practicing, my law firm represented in Baltimore the Hearst Corporation, which had a daily newspaper, a TV station, and two radio stations. So, I had to do a lot of work in advising the journalists what could or could not be put on the air in the newspaper. And I developed a relationship with journalists.

And then when I was in Tampa, I became very friendly with a young reporter there who was covering the bankruptcy court for the local NPR station. He then moved on to NPR to become a White House reporter, and now he's the Chief Financial Reporter. And then in Miami, I got to know a great reporter who now is at Planet Money for NPR. They exchange who are their experts.

And I think in representing the Hearst Corporation, I learned how to speak to journalists, what you can say, what you can't say, and maybe that's done me well. But I'm called on a lot, very rarely to go on air, mostly to provide background.

John Reed: [00:35:01] Speaking of going on air, though, you had a pretty momentous television appearance. Tell us about that.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:35:07] Yes, I was the principal person on a “60 Minutes” session on bankruptcies, especially in Florida, where Lesley Stahl interviewed me. And I was on the 15-minute segment; a lot more minutes than I think I would've wanted to be.

But I had been working with them, this is when I was vice president of research for the ABI. Worked with the producers for several months in getting them the information because there was no internet. We traveled around the courts to look at dockets, and I explained it and taught them and everything. And five days before they were going to do a taping, they asked me if I would be willing to be interviewed, and I was, and of course, I didn't realize how many people from my past, even from elementary school, contacted me as a result of being on 60 Minutes.

John Reed: [00:36:04] Well, at least it was Lesley Stahl and not Mike Wallace.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:36:07] Yeah, I was actually concerned. My law partners had some hesitancy if it had been Mike Wallace. They had a tendency to castigate everybody, but Lesley Stahl was a great journalist and did a lot of homework and totally controlled everything beautifully, and it was smooth.

John Reed: [00:36:27] So for your however many minutes of that 15-minute piece, how long did the recording take?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:36:32] Recording took three and a half hours. There were a lot of questions. It was really good. The producers had given her an outline, and she would look at the outline for a topic, start me on it, and she was so well-versed in what she had learned that she would have five or six follow-up questions that were not written down, that we then had a dialogue. And there were a few of them we went back on, a few of them asked for more explanations. We would take breaks, a lot of lights, and a lot of heat. A lot of re-makeuping that had to be done for my hairless head and her face, and it was just quite interesting.

John Reed: [00:37:16] So that's where you got the experience with makeup before the whole clown thing.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:37:19] That's right. I didn't know it.

John Reed: [00:37:22] We've talked a little bit about your first interactions with NPR and where that went, but talk about the importance to you of public broadcasting and public TV now.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:37:31] Well, I've always been a fan of public radio. Maybe I am a frustrated journalist. I love radio. And when I was first in Baltimore and then in Tampa, I became a volunteer for the local NPR stations. When I came to South Florida on the east coast, someone who was on the board of the NPR station got me involved as a volunteer, and then I got on the board, and then I wound up being chair of the board of WLRN, which is the NPR station for the whole southeast part of Florida, which I really enjoyed.

Because once you're off the board, you're off, I got on the board of South Florida PBS, which the TV is a separate thing, and I'm on the board there. And now I am the finance chair of the board. And to me, it's very important because I know it's become a little bit of a political football of late, but public media is there for the people, and it's free. And it's one of the few things that you get for free that people ask for donations, and especially for the TV public. TV stations now are all still both analog as well as being digital, so that it's one of the few media that inner city households and those that can't afford cable can still get on a television without a cable subscription.

And with the early childhood education that is on virtually every PBS station in the morning and early afternoon and mid-afternoon, that's the only early childhood education that's available for a great part of our population that can't afford daycare. It's critical, and also if you've ever seen, and I know you have, the Ken Burns specials and the Nature specials and the PBS NewsHour, it can't be replaced anywhere.

John Reed: [00:39:37] You're probably seeing, maybe getting communications from other finance people at other stations that are in these smaller communities. It's just got to be so distressing.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:39:46] It is very distressing. The government cut off all funding to PBS and NPR. For the larger metropolitan areas, it's an annoyance, but their endowments, their supporters, their underwriters, they're going to make it. They may change their programming, do a lot less original programming, fewer events, and things like that. But as it's only been a couple of months, and it's my understanding, as of last week, 33 rural or small community PBS stations had to shut down.

John Reed: [00:40:22] I don't know how to respond to that. It breaks my heart.

You also feel a very strong commitment to pro bono work. I know pro bono is certainly a worthwhile opportunity for lawyers to give back, but it offers benefits to other lawyers, too, especially newer lawyers. So, talk about your world of pro bono and what you've seen in other places with pro bono.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:40:43] I'm very lucky. Our firm has a strong pro bono policy, and there are a lot of other firms in South Florida that do it well. We have a pro bono committee, and if anybody has a pro bono case, it comes to the committee. If the committee approves it, then the associate that gets to work on it gets full credit for the hours that they bill on that as if it were a billing client. It encourages doing pro bono work with no penalty, and it allows some of the younger lawyers to do things that they may not be able to do for a big multinational or big company or a client that otherwise feels they want a more senior person to do it. It's very rewarding.

We all need to give back to the community, and in this day and age, where civil legal services are out of reach for a good part of the population, it's nice to feel the thank you that you get, the heartfelt thank you that you get, when you've successfully helped someone out of a problem.

John Reed: [00:41:54] Tell us about some of the pro bono work that you've done.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:41:57] I was also chair of the board—it's misnomered now—it's called Hispanic Unity of Florida. It started during the boatlift of the Cubans, but now more than 50% of the documented immigrants are not Hispanic. Doing a lot of pro bono work for immigrants. We do some bankruptcy work, and I have done just anything to do with commercial. We don't do immigration status work, but helping the immigrants deal with small business issues, setting up businesses, dealing with culture differences.

I also do a lot of pro bono work in the Turkish community, only because I've gotten to know the Turkish people. I speak a little of the language, and the word has spread that I understand their culture of doing business.

John Reed: [00:42:52] What we've just talked about, two of the most hot button issues these days— public television/public radio, and the immigrant community—and you're there helping. That's really wonderful.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:43:02] Well, I'm first generation, and I heard over the years my grandparents and my parents talking about when they came to this country, what it was like, not speaking the language. Not knowing anybody. Starting all over again. And you need a helping hand. You can't do it alone.

John Reed: [00:43:22] Chuck, you are a giver. Is that where your altruism comes from?

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:43:26] It does. Parents and grandparents. And it's reinforced by the fact that my wife, who grew up in a very traditional immigrant Italian household, had the same values. So, my own view, especially about spending time doing it, is reinforced by my wife's support for it.

John Reed: [00:43:50] I am going to go out on a limb here and say, I bet you're a great mentor to up-and-coming lawyers.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:43:55] I hope so. I do that a lot here. In my firm, there are five of us that are over 80 who are still practicing full-time, and one of our roles besides representing clients is to be the mentor. I also serve proudly now as the board chair of the Nova Southeastern Shepard Broad College of Law. And as a board, we have a mentorship program for law students. That's been very rewarding because when I was in law school, there were no mentors, and the faculty sometimes was not even approachable. Well, the faculty are now very approachable, but my 32 board members work very judiciously to do all we can do to help law students through the process.

John Reed: [00:44:47] Prior to us meeting Chuck, I had no knowledge of your law firm, but it sounds very progressive, both in terms of the pro bono billing credit, which for non-lawyers is an incredibly huge economic sacrifice and boon, depending on how you look at it, but also, having senior veteran people like you still practicing, not forcing you out the door or forcing you into an of counsel position or something like that. And then this commitment to mentoring. So, kudos to your law firm.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:45:17] Well, thank you. It's very unusual. I've only been here 14 years. I was attracted to it because of the culture. One of the very unique things, which only lawyers will understand, is every office is the same size except the corner offices, which are smaller. I happen to be in a corner office. The first-year associate who works next to me has a bigger office than I do.

John Reed: [00:45:43] Chuck, I'm going to ask you one last question. This has nothing to do with your age, but I understand you have a certain connection to prehistoric mammoths.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:45:53] Yes. This summer, my wife and I took a tour of the Badlands and the whole area around Mount Rushmore in South Dakota, and we went to the mammoth site, which is very unique. It was a pit that opened up in the earth and, prehistoric times, about 45 feet filled with water and a bunch of mammoths and other animals fell in. It's like a sinkhole, and over the millennia, it then filled in, and the unique nature of the land and the earth in South Dakota preserved everything. When it got discovered, they created this site for exploration and every year they go down another foot. They're at 20 feet.

So, this summer when I heard about this, we learned that every year they let people come out there to work for a week or two to help them be paleontologists. And I quickly signed up, and I got accepted. So, July 12th of next summer, I'm going out there for a week to become a paleontologist. Ice Age Cadet. That's what we're going to be called. And I gather, I get a T-shirt.

John Reed: [00:47:14] I hope so. I hope so.

Chuck, this has been a delight. Talking to you inspires me and makes me feel good, and I can't think of any better way to get into the Thanksgiving spirit. So, thank you for spending time with me and sharing all of your wonderful stories and Happy Thanksgiving.

Chuck Tatelbaum: [00:47:31] Thank you, and to everyone else as well. It's a wonderful holiday to celebrate.

John Reed: [00:47:37] From all of us at Sticky Lawyers and Rain BDM, I hope you have a happy Thanksgiving as well.

Speaking of gratitude, I would be grateful if you took a moment to please subscribe to Sticky Lawyers wherever you listen to podcasts, and leave a review or give us a rating. When you do, it helps people discover the show. And you can never have enough people around the Thanksgiving table.

Until next time, I'm John Reed, and you've been listening to Sticky Lawyers.

Director and Chair of the Creditors’ Rights and Bankruptcy Practice Group, Tripp Scott

For 59 years, Charles Tatelbaum has been one of the country’s foremost bankruptcy, creditors’ rights, and complex business litigation lawyers. He currently chairs the creditors’ rights and bankruptcy practice group at Tripp Scott and is recognized for representing Fortune 150 companies, as well as playing a critical role in several landmark bankruptcy cases. Chuck's extensive non-profit work includes leadership and board roles with South Florida PBS, Hispanic Unity of Florida, The Shepard Broad School of Law at Nova Southeastern University, and other civic organizations, reflecting his commitment to community service and the arts.